Introduction

In late November 2018, a friend journalist Clarissa Beretz invited me to a non-commissioned project. She had obtained air tickets to travel and accompany the meeting of the indigenous peoples of Mato Grosso. The meeting took place during the last week of November 2018 at the Xingu Indigenous Park, one of the largest indigenous territories in Brazil.

Through the president of the Associação Terra Indígena do Xingu (ATIX), Waré Wapichana, we stayed at the home of Chief Aritana Yawalapiti, the largest leader in the territory of the Upper Xingu during the 7 days that the meeting lasted.

It was an honor to be able to live for so many days with such a wise man and his family. Being able to share a little of his routine and kindness, listening to his words and understanding many of the shortcomings we have as a white Western society. Aritana is the Chief (greatest chefer) of the Yawalapiti people, a people who now live in the southern portion of the indigenous land.

After staying with the Yawalapiti people, we continue to the Kamayura village. There, we stayed for another week at the Shaman Mapulu Kamayura house, the first paje woman of the Kamayura people. Mapulu’s father, the chief and also paje Takuma Kamayura, was the one who passed on her knowledge when she was 15 years old.

Left: Chief Aritana Yawalapiti

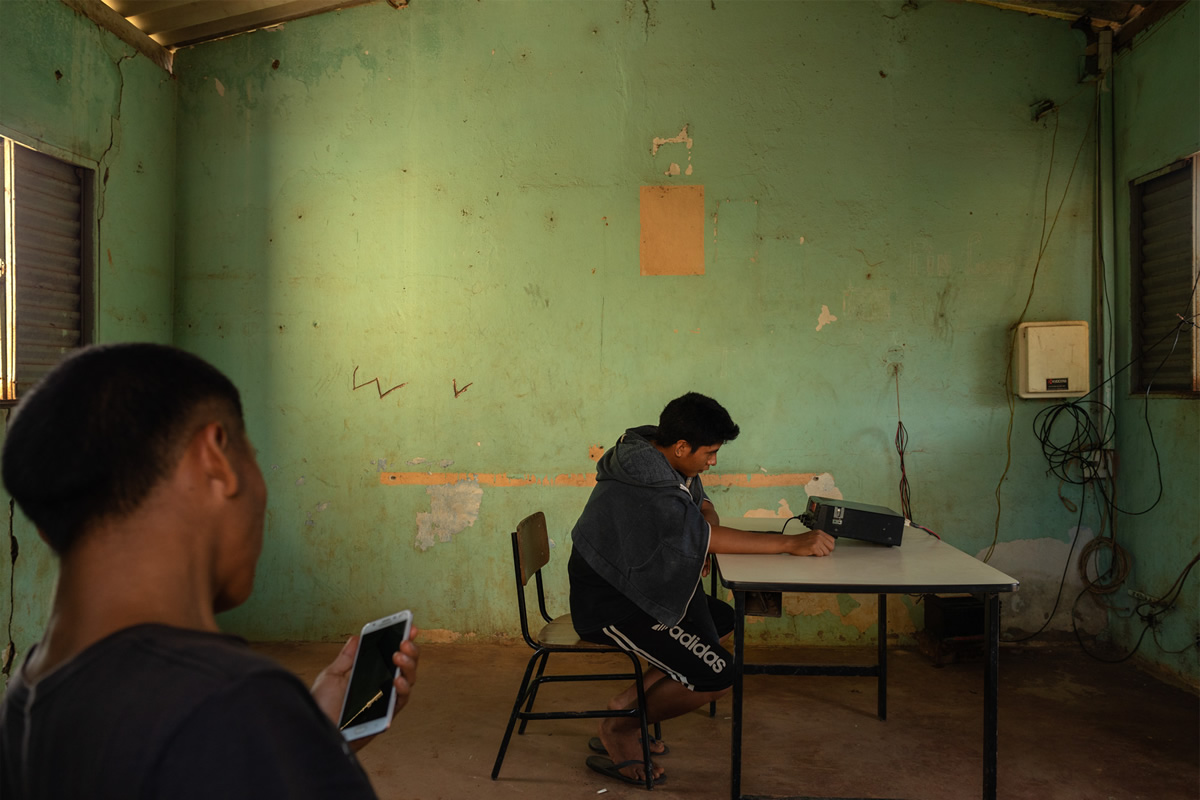

Thus, this is a photographic project that seeks to portray the current daily life of the Yawalapiti and Kamayura ethnic groups, peoples who share the territory of the Xingu Indigenous Park, a place that directly feels the pressures of Western culture on the people of Brazil and that suffers enormous threat from agribusiness and the large highways for transporting grains from crops to the surroundings of the Xingu territory.

Mato Grosso is going through a constant process of deforestation of original forests and its conversion into gigantic corn and soy plantations, parallel to the cattle breeding. Much of the burning and clearing of forests in the Amazon reported in 2019 occurred in the State of Mato Grosso. The Xingu Indigenous Land is also constantly threatened by the presence of illegal hunters, loggers and miners.

Today Brazil is going through one of the most politically complex and critical periods and there is a great relaxation in environmental norms and rules, in addition to the dismantling of inspection and deforestation systems throughout Brazil. Indigenous peoples are guardians of Brazilian forests. And they are constantly threatened precisely because they struggle to keep forests standing, through their cultural traditions of sustainable land use.

The Xingu Indigenous Land:

The Xingu Indigenous Park (PIX) is located in the northeastern region of the State of Mato Grosso, in the southern portion of the Brazilian Amazon. In its 2,642,003 hectares, the local landscape exhibits a great biodiversity, in a region of ecological transition, from the driest savannas and forests to the south to the Amazonian forest to the north, presenting savannahs, fields, floodplain forests, upland forests. and forests in Black Archaeological Lands. The climate alternates between a rainy season, from November to April, when the rivers fill and fish are scarce, and a period of drought in the remaining months, the time of the tracajá turtle and the great inter-village ceremonies.

South of the Park are the Xingu River, which forms a basin drained by the Von den Stein, Jatobá, Ronuro, Batovi, Kurisevo and Kuluene rivers; this being the main trainer of Xingu, when meeting with Batovi-Ronuro. The administrative demarcation of the Park was approved in 1961, with an incident area in part of the municipalities of Canarana, Paranatinga, São Félix do Araguaia, São José do Xingu, Gaúcha do Norte, Feliz Natal, Querência, União do Sul, Nova Ubiratã and Marcelândia.

The idea of creating the Park took shape in a round table convened by the Vice-Presidency of the Republic in 1952, which resulted in a preliminary project for a Park much larger than what finally came to fruition. Despite the legislative and executive powers of Mato Grosso being represented in this roundtable, including by its governor, the state began to grant, within this perimeter, land to colonizing companies. For this reason, when the Xingu National Park was finally created, by Decree nº 50.455, of 04/14/1961, signed by President Jânio Quadros, its area corresponded to only a quarter of the area initially proposed. The Park was regulated by Decree nº 51.084, of 7/31/1961; adjustments were made by Decrees nº 63.082, of 6/8/1968, and nº 68.909, of 7/13/1971, and the current perimeter was finally demarcated in 1978.

The hybrid category of “National Park” was due to the dual purpose of environmental protection and of the indigenous populations that guided its creation, the area being subordinated to both the official indigenous organ and the environmental organ. It was only with the creation of Funai (in 1967, replacing the SPI – Indian Protection Service) that the “National Park” came to be called “Indigenous Park”, turning then primarily to the protection of native sociodiversity.

In view of the peoples who live there, the Xingu Indigenous Park can be divided into three parts: one to the north (known as Baixo Xingu), one in the central region (the so-called Middle Xingu) and another to the south (the Upper Xingu).

In the south are very culturally similar peoples, comprising the Upper Xingu cultural area, formed by the Aweti, Kalapalo, Kamaiurá, Kuikuro, Matipu, Mehinako, Nahukuá, Naruvotu, Trumai, Wauja and Yawalapiti peoples. Despite their linguistic variety, these peoples are characterized by a great similarity in their way of life and worldview. They are also articulated in a network of specialized exchanges, weddings and inter-village rituals. However, each of these groups makes a point of cultivating their ethnic identity and, if the ceremonial and economic exchange celebrates Upper Xingu society, it also promotes the celebration of their differences.

The current Yawalapiti village is located further south, at the meeting of the Tuatuari and Kuluene rivers, a place of fertile land, about five kilometers from the Leonardo Villas Bôas Post. The Kamaiurá never left their occupation area, in the region where the Kuluene and Kuliseu rivers meet, close to the great Ipavu lagoon, which means, in the language of this people, “great water”. Today, the village of Kamaiurá is located about ten kilometers north of the Leonardo Villas-Bôas Post, approximately 500 meters from the south bank of the Ipavu Lagoon and six kilometers from the Kuluene River, on your right. The immediate Kamaiurá territory is the village, formed by the houses and the ceremonial courtyard, the neighboring forest, the Ipavu lagoon and the streams that flow into it.

A recent movement has also brought all the peoples of the Park together in the name of common interests. Indigenous organizations (especially the Associação Terra Indígena do Xingu) have established themselves as an important means of dialogue with national society and the promotion of educational projects, economic alternatives and protection of the territory.

Shaman Mapulu Kamayura

About Renato Stockler

After an intense afternoon downpour, I went into the street where my parents lived and, in wonder, watched the spectacle that the sun imprinted everywhere in shades of orange. I must have only been about three years old but I can remember, until this day, how I was enchanted by the glittering reflections on the wet floor.

The years passed and I had contact with many of the different realities that such a vast and complicated territory like that of Brazil has. Disturbed by the origins of inequality and other social issues, I decided to study journalism. In the Faculty of Social Communication, I had the privilege of receiving a critically discerning formation committed to contemporary society. It was there that the sense of wonder at light and form, dormant since childhood, was reawakened by contact with the fundamental principles of photography.

As a graduate, I produced photographs for newspapers, books, editorial publications, branding content, portraits, documentary and corporate portfolios, sustainability studies for impact assessment consultants, and other companies as well as doing photography direction for audiovisual projects, films, documentaries, series, and entertainment. Through their links to human rights, economy, education, and urban issues, many of these projects have allowed me, and indeed continue to allow me, to search for a deeper understanding of our times.

Today, I continue to be motivated not only by the capacity of light to convert something commonplace into something extraordinary but principally by the possibility of creating documents and contemporary narratives about environmental, behavioral and humanitarian concerns. In

conjunction with commercial projects and due to popular initiatives and the practices and positive agendas of some organizations, photography and audiovisual projects have become the central expressions for the realization of a very clear purpose: to construct narratives by respecting and listening to those who experience different realities within the same territory.

That is the place that photography occupies in my creative process and where I deposit my attention and critical observation.

You can find Renato Stockler

on the Web :

Copyrights:

All the pictures in this post are copyrighted to Renato Stockler. Their reproduction, even in part, is forbidden without the explicit approval of the rightful owners.

from 121clicks.com https://ift.tt/2zUuQGd

via IFTTT

0 comments:

Post a Comment